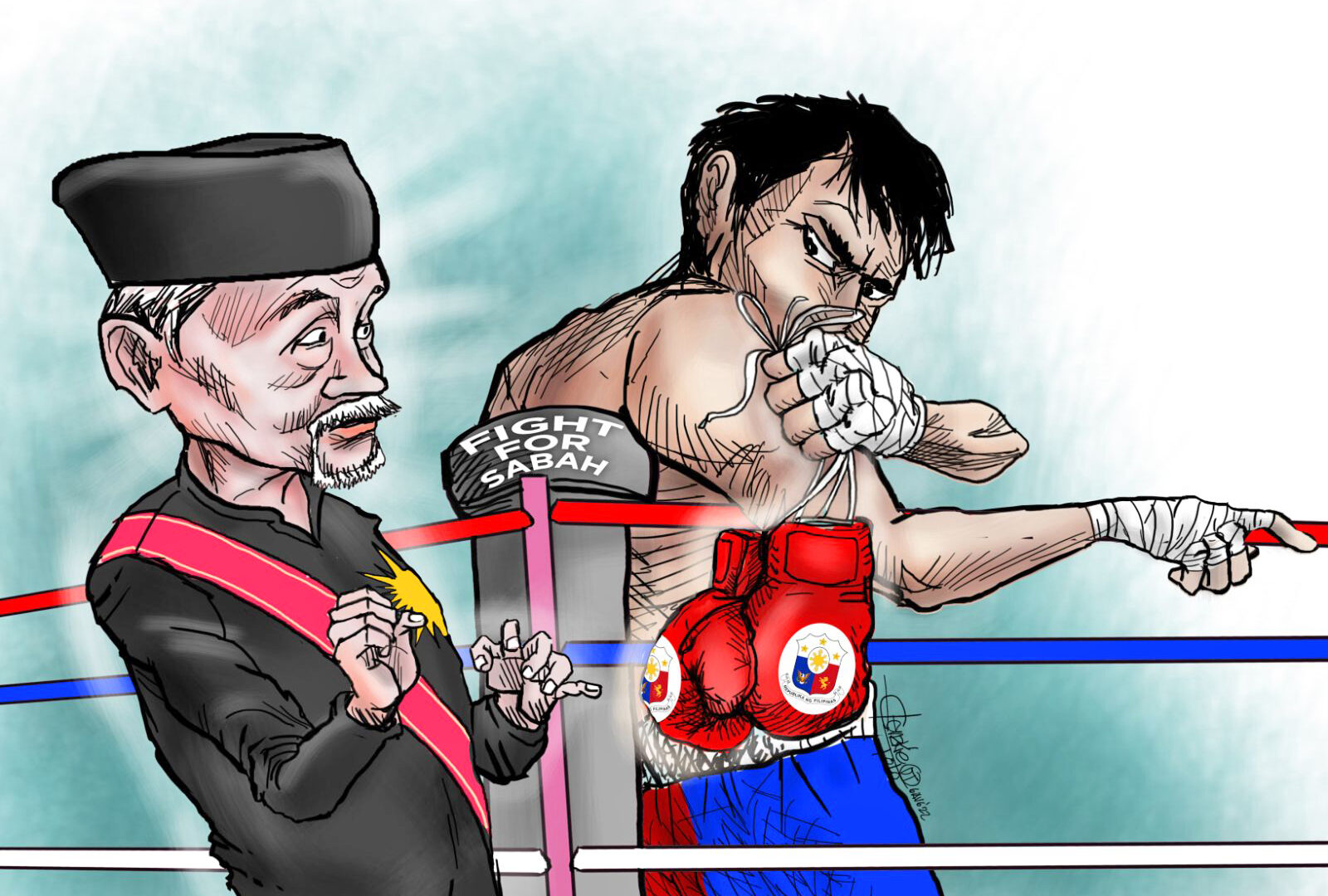

Last month, a Paris-based international arbitration tribunal awarded the heirs of the Sultan of Sulu $14.9 billion in a case the heirs filed against Malaysia over North Borneo, which Malaysia calls Sabah.

The heirs are encountering difficulty in enforcing the award, and are quietly seeking the help of the national government.

Before the government moves, however, an important internal concern should first be resolved.

Long before Malaysia claimed ownership of North Borneo in 1963, the heirs have been pressing the sovereignty of the Sultanate of Sulu over North Borneo.

From a legal perspective, that means the descendants of the Sultan of Sulu are supposed to be citizens or subjects of the sultanate.

Realizing the difficulty of their position, the heirs signed an agreement with the Philippines in August 1962. Under that agreement, sovereignty over North Borneo was transferred to the Philippines.

While sovereignty over North Borneo was transferred to the Republic of the Philippines, ownership of the land itself remained with the heirs.

The 1962 deal stipulates that the Philippines will press its claim to North Borneo before the international community, and if the Philippines reneges on that undertaking, sovereignty over North Borneo reverts to the Sultanate of Sulu.

With North Borneo under Philippine sovereignty, the heirs had to decide if they remained citizens of the Sultanate of Sulu, or become citizens of the Philippines.

From the way the heirs comported themselves after the 1962 agreement was signed, they acknowledged their being Filipino citizens. This is extant in their personal documentation through the decades since 1962. A number of them even held public office in the Philippines after 1962.

Under Presidents Diosdado Macapagal and Ferdinand Marcos Sr., the Philippines consistently pressed its claim to North Borneo (eventually called Sabah) before the international community.

In July 1963, the Manila Accord was signed by the Philippines, Indonesia and the Malaysians. It stipulated that the incorporation of Sabah into Malaysian territory is subject to the Philippine claim to the same.

Later in 1967, the administration of President Marcos Sr. planned to take Sabah by force, but the plan was scuttled by an exposé made by then Senator Ninoy Aquino in March 1968.

In 1968, Congress enacted Republic Act 5446 which declared that Sabah remains under Philippine sovereignty.

The 1973 Constitution recognized Sabah as part of Philippine territory.

In August 2011, the Supreme Court of the Philippines declared that the Philippines has never abandoned its claim to Sabah.

After Malaysia arbitrarily stopped paying rent for Sabah in 2013, the heirs eventually sued Malaysia before the Paris-based international arbitration tribunal.

As stated earlier, the heirs won their case, and they obtained an award of $14.9 billion. The lawyers of the heirs are now trying to enforce the judgment against Malaysian assets in Europe.

Last month, however, the secretary-general of the Sultanate of Sulu said the Sabah claim is now a “private” matter because on 12 February 1989, the sultanate issued a resolution revoking the 1962 transfer of sovereignty over Sabah to the Philippines. According to him, the Philippines reneged on its contractual undertaking to press the Philippine claim to Sabah.

However, and as discussed earlier, the Supreme Court categorically declared in 2011 that the Philippines has never abandoned its claim to Sabah. This clearly means there is no valid ground for the 1989 revocation of the 1962 agreement.

Moreover, if the 1962 deal is deemed revoked, Sabah is no longer under Philippine sovereignty, and the Philippine citizenship of the heirs is questionable. Should this be so, then the Philippine government cannot help the heirs press their claim to Sabah, or assist them in the enforcement of the award rendered by the Paris-based arbitration tribunal. Funds of the Philippine government cannot be spent to support alien interests.

Ultimately, the heirs of the Sultan of Sulu must make up their mind on this serious concern before the Philippine government can assist them in enforcing the aforesaid arbitration award.