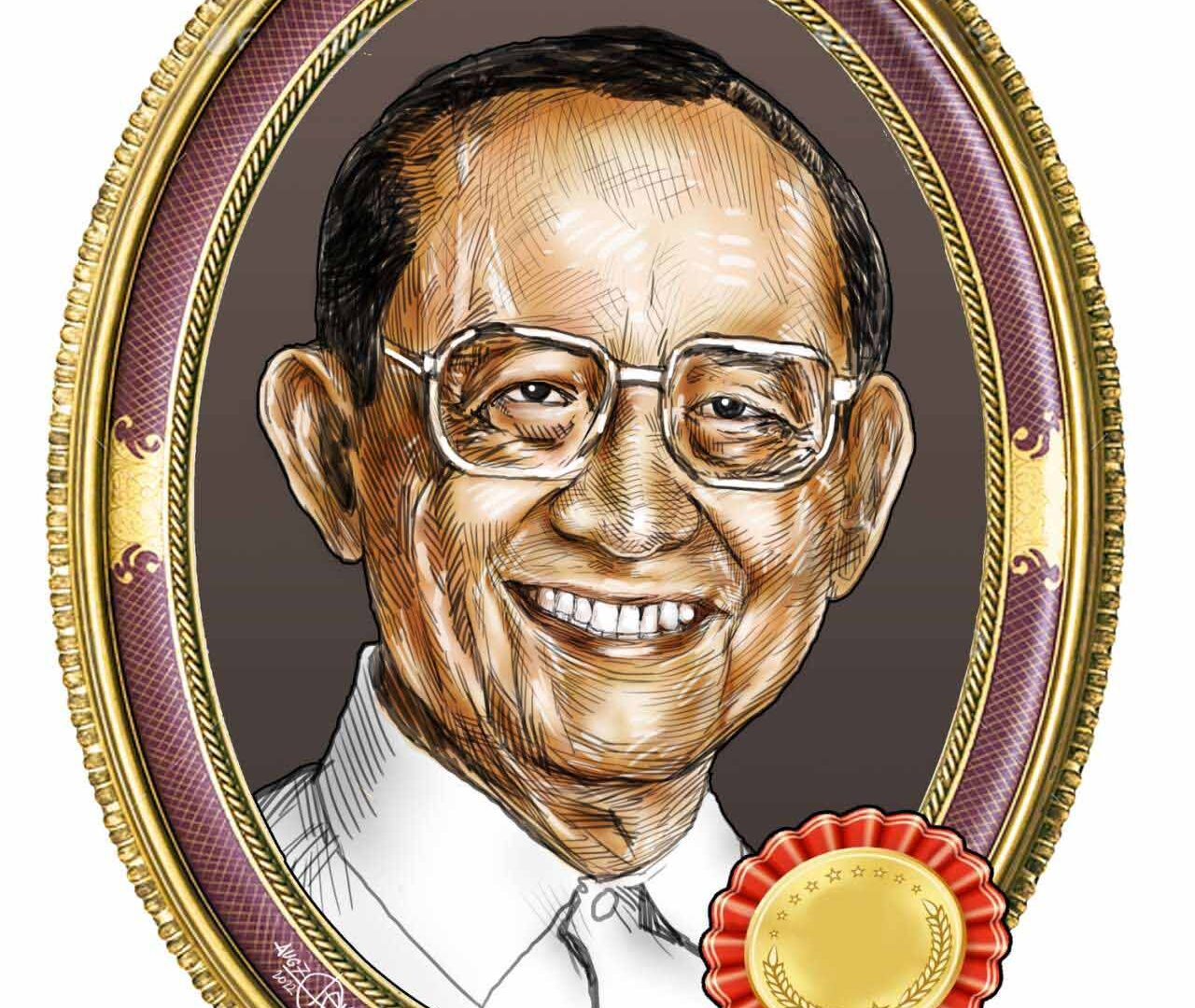

Numerous tributes and analyses point to the recently departed Fidel V. Ramos as the Philippines’ best president thus far.

Is this claim valid? Let us count the ways.

The first sign that Ramos was on to something great was when he made the crucial decision to join Juan Ponce Enrile in sparking the 1986 Edsa Revolution, which restored democracy to the country after 14 years of authoritarianism.

In the next six years as Armed Forces chief, he would be leading the military in warding off seven coup attempts by rightist elements in their own backyard.

His victory in 1992 as 12th Philippine president drew a protest from his closest rival, but when things settled down, Ramos started his term on a high note.

In his newspaper column, former Banko Sentral ng Pilipinas deputy governor for the Monetary and Economics Sector Diwa C. Guinigundo recalled Ramos taking on the role of a salesman persuading a skeptical world:

“But unlike a salesman, FVR sold products of his own making. We recall joining those fund-raising exercises in Asia, Northern America and Europe for both the national government and some government corporations. With a hollow economy, volatile consumer prices and weak public finance, selling bonds was a tall order. It was likely to be undersubscribed. Ours were junk bonds with stiff risk premia, which means it was very expensive to borrow from abroad. But we found a good messaging, all ostensibly because of a single unifying element: FVR.”

The result, as Guinigundo put it, was an “oversubscription of the country’s global bonds.”

A paper published by the International Monetary Fund in 2000 said that during the Ramos presidency, the Philippines “emerged” from slow growth and economic imbalances and survived the 1997 Asian financial crisis.

And in another paper, from the World Bank in 2008, the Philippines, from 1992 to 1998, “came closest to breaking out of its ‘sick man of Asia’ image.”

The IMF said that “by 1996, growth went up to almost six percent and the external position had strengthened, with rapid export growth and rising reserves.”

According to the Philippine Statistics Authority, gross domestic product was 0.3 percent in 1992; 2.1 percent in 1993; 4.4 percent in 1994; 4.7 percent in 1995; 5.8 percent in 1996; and 5.2 percent in 1997.

On the perennial problem of corruption, was Ramos successful in at least minimizing it?

Transparency International’s Corruption Perception Index showed that the Philippines, from 1994 to 1998, had an average score of 2.69 to 3.3 out of 10, which was then the highest:

• 1995: Rank 36; 2.77

• 1996: Rank 44; 2.69

• 1997: Rank 40; 3.05

• 1998: Rank 55; 3.3

Not quite, but the effort was apparent.

Ramos made peace with the Communist Party of the Philippines and the Moro National Liberation Front. To prove his sincerity, he signed into law Republic Act 7636 which repealed the Anti-Subversion Law.

His administration actually went through the most trying challenge, the power crisis, which he tried to solve by issuing licenses to independent power producers to construct power plants within 24 months.

Ramos issued supply contracts that guaranteed the government would buy whatever power the IPPs produced under the contract in US dollars to entice investments in power plants.

However, this spawned a bigger problem during the Asian financial crisis as demand for electricity contracted and the peso lost half of its value.

But perhaps his lasting legacy is one closest to our heart: FVR understood the adversarial role of media. He was, as reporters who covered him attested, a most accommodating chief executive — always available for interviews and never one to issue a “no comment” response to the most intimidating questions.