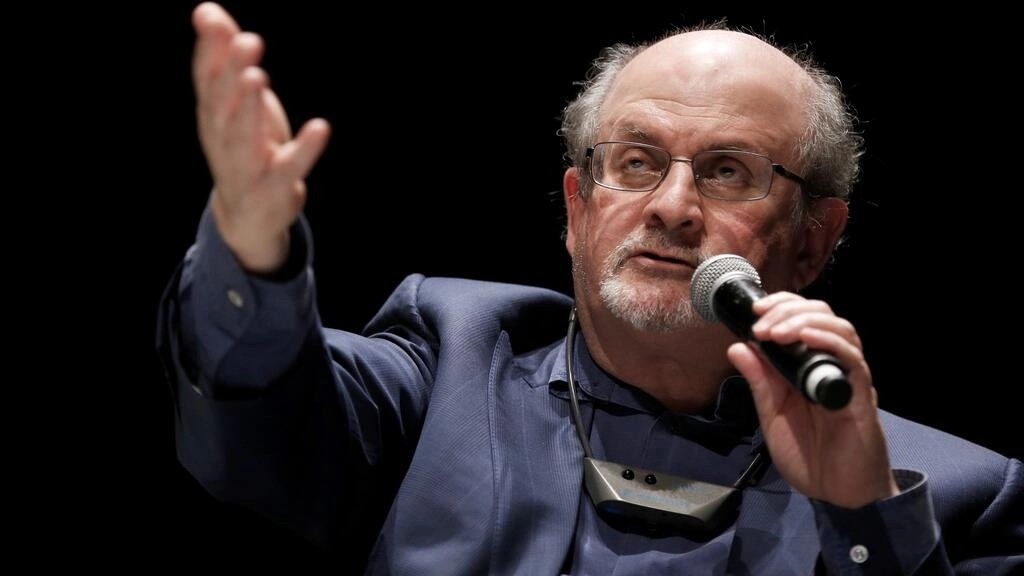

Salman Rushdie, who spent years in hiding after an Iranian fatwa ordered his killing, was on a ventilator and could lose an eye following a stabbing attack at a literary event in New York state Friday.

The British author of “The Satanic Verses”, which sparked fury among some Muslims, had to be airlifted to hospital for emergency surgery following the attack.

His agent said in a statement obtained by The New York Times that “the news is not good.”

“Salman will likely lose one eye; the nerves in his arm were severed; and his liver was stabbed and damaged,” said agent Andrew Wylie, who added that Rushdie could not speak.

Carl LeVan, an American University politics professor attending the literary event, told AFP that the assailant had rushed onto the stage where Rushdie was seated and “stabbed him repeatedly and viciously.”

Several people ran to the stage and took the suspect to the ground before a trooper present at the event arrested him. A doctor in the audience administered medical care until emergency first responders arrived.

New York state police identified the suspected attacker as Hadi Matar, a 24-year-old from Fairfield, New Jersey, adding that he stabbed Rushdie in the neck as well as the abdomen.

The motive for the stabbing remains unclear.

An interviewer onstage, 73-year-old Ralph Henry Reese, suffered a facial injury but has been released from the hospital, police said.

The attack took place at the Chautauqua Institution, which hosts arts programs in a tranquil lakeside community 70 miles (110 kilometers) south of Buffalo city.

“What many of us witnessed today was a violent expression of hate that shook us to our core,” the Chautauqua Institution said in a statement.

LeVan, a Chautauqua regular, said the suspect “was trying to stab him as many times as possible before he was subdued,” adding that he believed the man “was trying to kill” Rushdie.

“There were gasps of horror and panic from the crowd,” the professor said.

A decade in hiding

Rushdie, 75, was propelled into the spotlight with his second novel “Midnight’s Children” in 1981, which won international praise and Britain’s prestigious Booker Prize for its portrayal of post-independence India.

But his 1988 book “The Satanic Verses” transformed his life when Iran’s first supreme leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini issued a fatwa, or religious decree, ordering his killing.

The novel was considered by some Muslims as disrespectful of Islam and the Prophet Mohammed.

Rushdie, who was born in India to non-practicing Muslims and today identifies as an atheist, was forced to go underground as a bounty was put on his head — which remains today.

He was granted police protection by the government in Britain, where he was at school and where he made his home, following the murder or attempted murder of his translators and publishers.

He spent nearly a decade in hiding, moving houses repeatedly and being unable to tell his even his own children where he lived.

Rushdie only began to emerge from his life on the run in the late 1990s after Iran in 1998 said it would not support his assassination.

Now living in New York, he is an advocate of freedom of speech, notably launching a strong defense of French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo after its staff were gunned down by Islamists in Paris in 2015.

The magazine had published drawings of Mohammed that drew furious reactions from Muslims worldwide.

Global leaders voiced anger over the attack on Rushdie, with French President Emmanuel Macron saying the author “embodied freedom” and that “his battle is ours, a universal one.”

British leader Boris Johnson meanwhile said he was “appalled,” sending thoughts to Rushdie’s loved ones and praising the author for “exercising a right we should never cease to defend.”

US National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan called it a “reprehensible attack,” adding that “all of us in the Biden-Harris Administration are praying for his speedy recovery.”

An ‘essential voice’

Threats and boycotts continue against literary events that Rushdie attends, and his knighthood by Queen Elizabeth II in 2007 sparked protests in Iran and Pakistan, where a government minister said the honor justified suicide bombings.

The fatwa and other threats failed to stifle Rushdie’s writing and inspired his memoir “Joseph Anton,” named after his alias while in hiding and written in the third person.

“Midnight’s Children” — which runs to more than 600 pages — has been adapted for the stage and silver screen, and his books have been translated into more than 40 languages.

Suzanne Nossel, head of the PEN America organization, said the free speech advocacy group was “reeling from shock and horror.”

“Just hours before the attack, on Friday morning, Salman had emailed me to help with placements for Ukrainian writers in need of safe refuge from the grave perils they face,” Nossel said in a statement.

“Our thoughts and passions now lie with our dauntless Salman, wishing him a full and speedy recovery. We hope and believe fervently that his essential voice cannot and will not be silenced.”