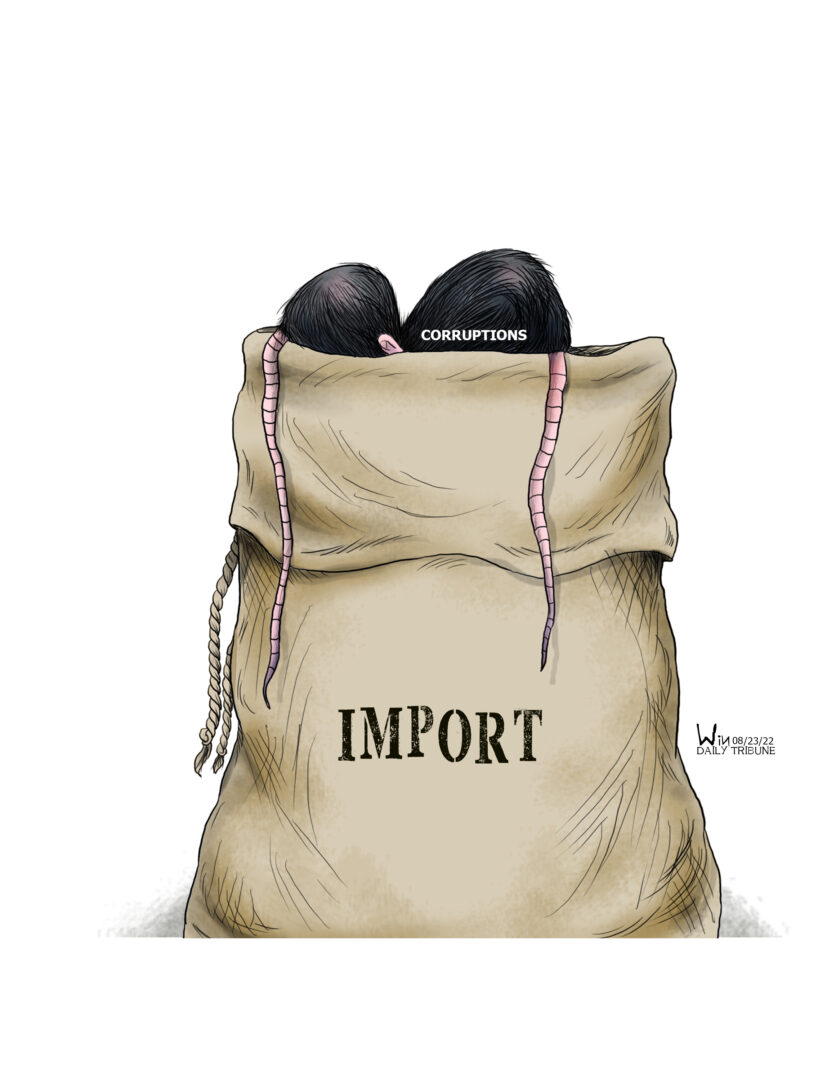

Importation done through government has always been a source of controversy as the recent sugar importation fiasco had shown.

The Sugar Regulatory Administration approved the importation of 300,000 metric tons as a response to the surge in the price of sugar amid a supposed shortage that local producers said did not exist.

Hoarding of the product to create an artificial supply shortfall has become evident.

In the first year of former president Rodrigo Duterte, an identical situation happened, but which involved the staple rice, prices of which then went through the roof.

The conflict was between Secretary to the Cabinet Leoncio Evasco, who was also head of the National Food Authority Council, a Cabinet-level policy making body of the grains agency, and National Food Administrator Jason Aquino.

Both eventually resigned or were asked to resign by President Duterte, who warned at the height of the friction that he would not allow even a whiff of corruption in his administration.

Evasco wanted rice importation via government-to-private mode, saying this was less prone to corruption, while Aquino wanted the run of the mill government-to-government importation.

Evasco then issued a confidential letter to President Duterte detailing how Aquino had allegedly diverted P10 million worth of NFA rice for typhoon-prone Eastern Visayas to private Bulacan traders.

After a government investigation, led by the Department of Agriculture, it was also discovered that traders then were buying grain from farmers at P18 per kilo and selling these in the market for P36, or a profit of P200 for every 50 kilos.

The hands of rice cartels were found to be behind the artificial rice shortage and the subsequent effort to bring in imported rice.

Eventually, the solution was to allow private importation and the removal of quotas, which was replaced by tariffs that subsequently led to the reduction of grain prices in the market while helping government raise revenues.

The government may well adopt a similar scheme for sugar, which has obviously replaced grains, now being targeted as a source of importation kickbacks.

The scheme was reviled by grains smugglers who rode on the NFA importation and the cohorts of corrupt officials who benefitted from rice imports.

Through NFA, the country became the biggest importer of rice despite the nation being an agricultural economy.

Before rice tariffication, NFA, as chief importer of the grain, incurred a total of P187 billion in tax subsidies from 2005 to 2015, or an average of P19 billion a year. According to government estimates, the NFA lost around P11 billion annually before the tariffication law.

Short-term transition challenges, such as the drastic drop in palay farmgate prices, happened during the implementation of the law.

Income derived from the law was used to provide loan programs for local governments to buy farm harvests.

Giving to private sector the ability to import commodities when they need these also removed discretion from government officials.

As anywhere in government, leaving too much to the judgement of functionaries comes with it huge temptations to make money.